Within five days, three things happened that turned my life upside down. My sister was diagnosed with bile duct cancer, my daughter found out she was pregnant with identical twins, and a daughter whom my brother had fathered forty years before found him (she’d been put up for adoption at birth).

Within five days, three things happened that turned my life upside down. My sister was diagnosed with bile duct cancer, my daughter found out she was pregnant with identical twins, and a daughter whom my brother had fathered forty years before found him (she’d been put up for adoption at birth).

Immediately, the title, The Arithmetic of Family, popped into my mind. The additions and subtractions within a family. Like a Dr. Seuss book — people were coming in, people were going out. I could see funny little Dalmatians wearing red and blue hats, walking on their hind legs, entering a house, leaving a house.

It took two and a half years to write the memoir my title was leading me to write. But when I’d finished, I realized I had not written the memoir my lifelong preoccupation was leading me to write.

I tell beginning writers: You have to write about what keeps you up at night. I had not followed my own advice.

At this point, there were three sections in my book. I cut two — which left me with a haiku! No, not really. I was left with a memoir about my older sister, Brenda, and me — the book I’d always wanted to write but didn’t feel I had the right to write.

I’d explored the subject of sisters in my first novel, The Slow Way Back, using some details from my life and my sister’s life to invent a work of fiction. But I was working through the material at a distance.

What would happen if I got close, made myself susceptible to change and loss, re-inhabited those memories?

*

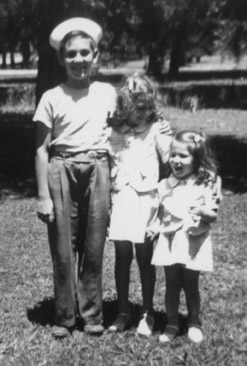

My sister and I were raised to be close. All our lives, we heard from our mother how close she was to her sisters, how close her mother was to her sister. In our family, sisters matter. We borrow each other’s bracelets, braid the other’s hair, play piano duets.

At the same time Brenda and I were being raised to be close, we were also being made finely distinct. Our parents – in fact, everyone in our world — constantly told us, “Brenda, you are your father to a T!” and “Judy, you are just like your mother!”

When I finally came to understand how we were set up for both inner and outer conflict – how do we stay close when we’re so different? – my book began to take shape. I’d found the narrative thread. The unexamined emotions. All that I had skirted in the earlier version of my memoir and in my first novel.

Now that I was getting clearer about the forces that had shaped Brenda’s and my relationship, maybe I wouldn’t feel the need to assign blame when I wrote about our conflicts. Maybe I wouldn’t struggle with what was appropriate to reveal, censor myself in an overzealous effort to protect others, worry about how I came across. I could even use the journal entries I’d made every night during the four months my sister was dying.

Still, while I was recalibrating my memoir, I sometimes heard Brenda’s voice in my head: “Judy, you know that’s not how it happened.” Was I taking liberties? Embellishing? Deceiving myself? I know that memory is often misleading. The very act of remembering can alter what actually occurred.

In the end, all I could do was keep my eye on one goal: Tell the truth, as I know it, about our relationship — the mysteriousness of our connection, its empty places, the divine harmonies.